The Psychiatric Interview / The Medical Interview

When interviewing any patient, whether in a psychiatric setting, or a

medical setting, the interviewer faces a number of options as to how best to

approach the interview, what the goals of the interview should be, how best to

maximize the finite and usually limited time available. There are as many

interview styles as there are interviewers and each style captures something

unique about the relationship between doctor and patient.

At each moment in the interview the interviewer faces a number of

opportunities and pitfalls, which can either deepen trust and understanding or

create greater difference and defensiveness. Probably the greatest mistake most

interviews make is asking too many too specific questions, turning the interview

into an interrogation.

In principle it is better to start with open-ended questions and follow

up on what the patient chooses to reveal about themselves. In practice this may

be more difficult than it seems. With practice, it becomes quite natural and

spontaneous.

All patients have a need to be understood and want to tell “their

story”. We might call this the “narrative imperative.” This is especially

manifested when someone comes to a doctor for help. But we need to appreciate

that most people do not know the kind of help they need, nor do doctors know

without listening carefully. There may be some dancing around the issues, or

back and forth volleying while the doctor tries to find out how forthcoming the

patient is prepared to be and the patient tries to find out how attentive the

doctor is prepared to be to their “inner self”. Even the most guarded paranoiac

wants to be understood.

It is thus tempting for the doctor to launch into a question and answer mode

when the patient initially hesitates. Communications specialists observing

doctor-patient interviews that this usually takes place in the first seconds of

an interview, not in minutes, and that even if patients start to elaborate their

concerns, doctors usually interrupt and direct the interview within the first

minute. Most medical interviewers are like the Joe Friday, the LAPD detective

of Dragnet fame: “Just the facts, Ma'me.” A more appropriate detective role

model might be Columbo, who though a bit rumpled, always listened patiently to

the story, then came back with follow-up questions.

The Minimal Activity Technique

The Minimal Activity Technique is a way of disciplining ourselves to let

the patient tell their story. It serves as a reminder that patients come to us

to talk and we can listen. We control the interview with a light touch. We

have two ears and one mouth for a reason and should probably use them in that

proportion.

The open-ended question: Recognizing that there is not one standard way

to interview patients, the interviewer should select an opening open-ended

question to start the interview. “Why have you come for help? “ “How can I

help you?” “Can you tell me something about yourself and your concerns?” “What

would you like to talk about today?” are all appropriate opening open-ended

questions.

Volleying or Dancing or Sparring: One may expect in the opening moments

of the interview the patient to clarify what is expected. Patients will often

ask, “What do you want to know?” which many doctors will take as a cue to

abandon the open-ended approach and launch into 40 questions and 40 answers.

This is a mistake. It reflects the doctors anxiety rather than confidence. It

is better to acknowledge the tension with another open-ended invitation.

“Whatever you feel is important?” or “Whatever you would feel most comfortable

talking about.” Often interviews will want to “make the patient feel

comfortable” by starting with chit-chat. This is also a mistake. An interview

that starts superficially usually stays superficially. If the doctor signals

that she or he is uncomfortable with feelings, the patient will pick up on

that. No one will feel comfortable talking about the humiliation of their

divorce or how hurt their were by childhood trauma right away, but they will be

testing the interviewer to see if this might be a place where they can feel

safe.

Stage One: Active listening. One the patient feels comfortable, the

interviewer can relax and listen to the patient’s narrative. Patients will

usually talk uninterrupted for many minutes if they feel they are being listened

to. The manic patient may talk forever and need to be interrupted. The

obsessive patient may give more details than we can initially make sense of,

and eventually need to be redirected, but listening precedes redirection.

Stage Two: Non-verbal encouragement. After the patient has been

talking for several minutes, they may stop or pause. This is not yet an

occasion to switch to the Q and A format? There will be a temptation to clarify

what the patient has said, but that is not necessary at this point. At this

point in the interview, it is better to encourage the patient to continue

talking and this can usually be done with a gesture like leaning forward,

looking at the patient directly and expectantly. The patient will usually

resume talking, and the interviewer can go back to active listening.

Stage Three: Verbal encouragement. After a period of active listening,

escalation to non-verbal encouragement perhaps several times, the patient may

pause again, uncertain about how to proceed. It is still not time to ask direct

questions. It may be more appropriate here to give some sort of verbal

encouragement: “Go on” “Is this difficult to talk about” “Can you say more

about that?” “What else?”

Caution: Stay with feelings. One of the biggest mistakes a medical

Joe Friday can make is to change the subject when patients begin to show

feelings, sadness especially but even anger or other feelings. . Patients will

be inclined to do this themselves. A supportive gesture, like offering a

tissue, is an acknowledgement of the feelings, but may suggest that tears should

be wiped away, so we can get on with fact-gathering. It may be better to ask,

“Can you put words on those feelings?” or at least to acknowlege in words what

you are observing: “This must be difficult to talk about.” or “You still have

feelings about this.”

Stage Four: Indirect question. After some time, the interviewer begins

to get some sense about how the patient is viewing their situation and is also

trying to make sense about what is being said. Indirect questions are

extensions of verbal encouragement and transitions to more direct questions.

Indirect questions facilitate the narrative by helping the patient begin to

observe what they are reporting. “You mentioned your mother, but haven’t said

anything about your father.” “How did you feel when you received the news?”

Stage Five: The Direct question. There are many options the

interviewer has before asking direct questions. By the time it is necessary to

ask direct questions, the patient will have told the doctor much of the needed

information, and the patient by tell his story in his way has also told the

doctor how they understand themselves and their situation. Although time has

been “lost” by letting the patient talk, much important information (and

understanding) has been gained. The direct questions that the doctor then asks

will be more meaningful for the patients and for the patience shown.

t=0 Establish rapport: Open –ended questions

Expect some volleying

Minimal activity technique

t=10 Think about Differential Diagnosis

t=15 Screening questions

t=20 Developmental history

t=25 Mental Status Questions pertinent to Diff Diagnosis

t=30 Feedback about what has been learned

Building a History:

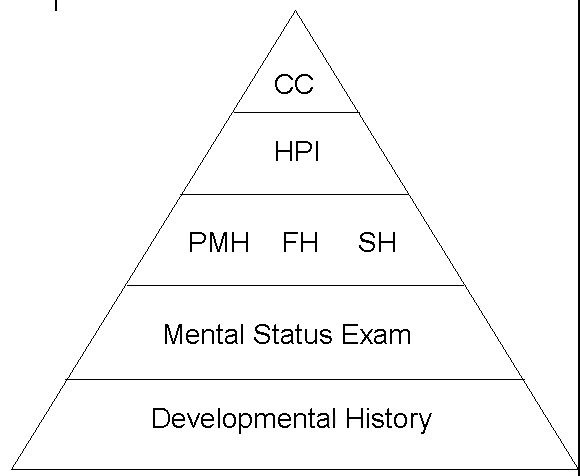

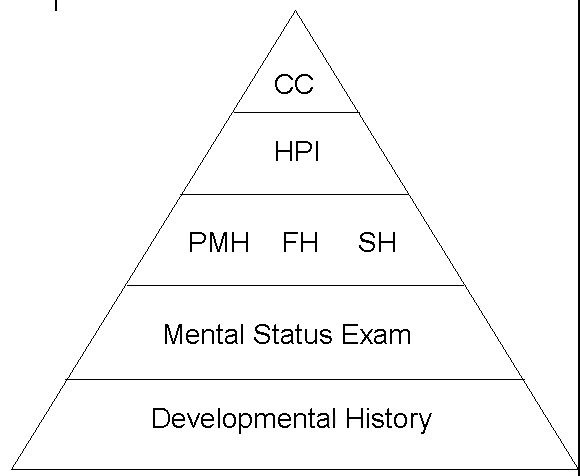

Building a History: By medical convention, the presentation of a history is in a certain border, starting with the chief concerns (not the chief complaint, please), progressing through the history of the present illness, the past medical history, the family history, social history, exams (physical exam, mental status exam, laboratory exams) and the Developmental History. Conceptually the Developmental Life History (or biography or patient narrative) is the foundation of the history we build with the patient. See more about the Developmental History and Repetition Compulsion.