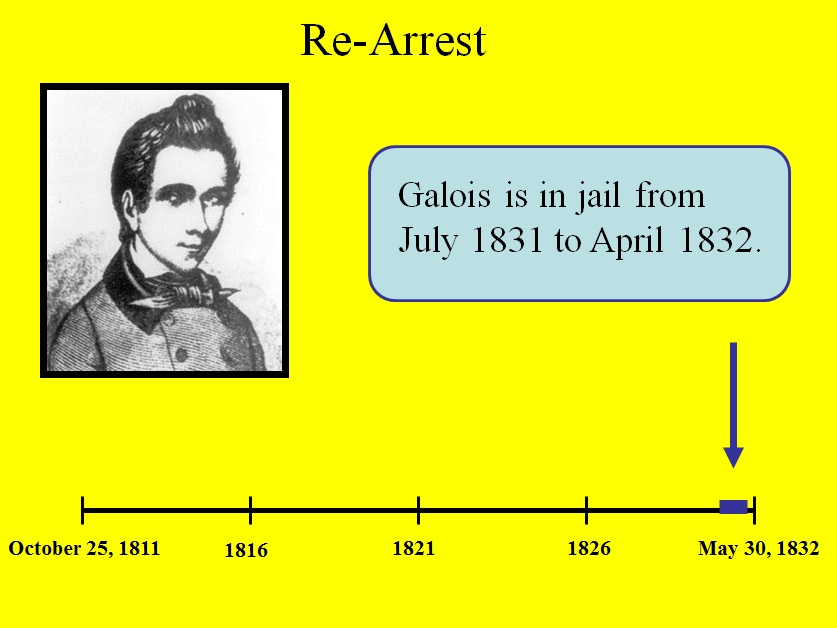

The republicans were organizing demonstrations for the celebration of Bastille day on July 14, 1831. Arrests were made of those thought to be the most threatening. Galois was found wearing his old National Guard uniform and carrying several weapons. He was arrested and charged with possession of illegal arms and wearing a uniform to which he was not entitled. He was detained for three months until his trial in October 1831. He was found guilty, appealed, and lost. He would remain in jail until April 1832.

Galois spent most of his time in Sainte-Pelagie Prison. He passed much of the time by walking up and down the yard, in meditation. He sometimes drank to excess with his cell-mates, and would then faint. His sister Nathalie-Thedore visited him often in the prison.

In the spring of 1832, a cholera epidemic swept through Paris. On March 16 Galois was transferred as a prisoner on parole to a nearby clinic. A doctor by the name of Jean-Pouis Poterin-Dumotal, who lived with his family in the same street, worked there. Galois met the doctor's daughter, Stephanie, and fell in love with her. The only evidence of the relationship are two letters from Stephanie, that Galois must have torn up in a moment of rage. He regretted this later, and tried to reconstruct the content. The letters indicate that initially Stephanie had encouraged Galois, but later lost interest. Galois was released from prison on April 29, 1832. He had one month left to live.

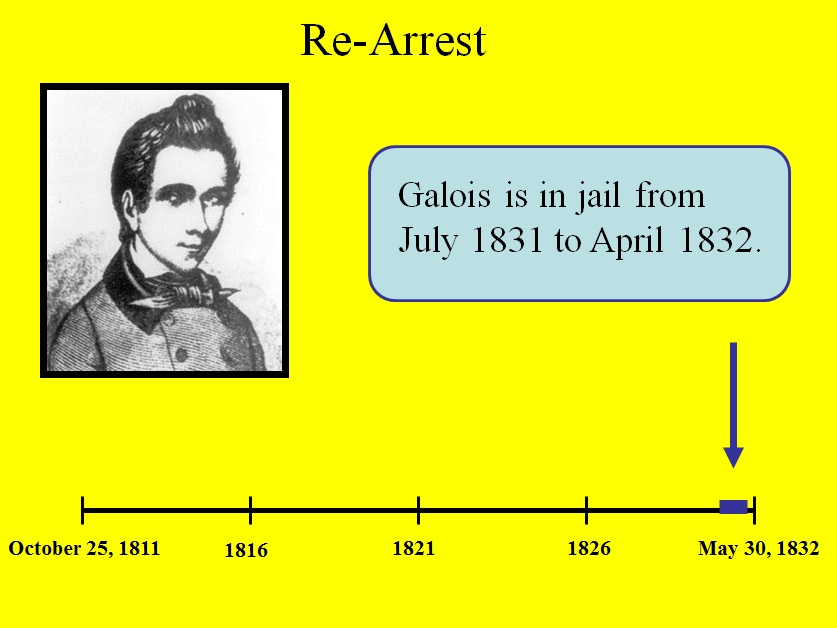

On the evening of May 29, 1832, Evariste Galois composed three letters. He was to fight a pistol duel the next morning and his letters speak of his impending death.

(1) The first letter is addressed to all republicans and states:

"I beg my patriotic friends not to chide me for dying in any other way than for my country. I die, the victim of a cruel coquette, and of two of her victims. My life fades away amidst trivial gossip. ... Adieu! Life was dear to me, for the common good. Pardon for those who killed me. They were acting in good faith."

(2) The second letter is addressed only to the initials "N.L." It states: "I have been challenged to a duel by two patriots ... I cannot refuse."

(3) The third letter is to his friend, Auguste Chevalier, and concerns mathematics.

He gave a brief summary of the memoire he had deposited at the Academy, adding some new theorems and conjectures covering seven pages. He concluded: "I do not have enough time and my ideas are not sufficiently well developed in this area, which is enormous."

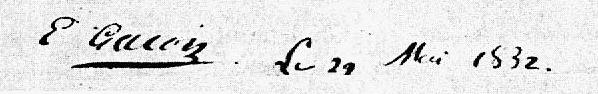

On the morning of May 30, 1832 at a distance of 25 paces, Evariste Galois was shot in the abdomen. He did not die instantly. He was taken to the Cochin Hospital by someone. It is unclear who took him to the hospital; some think it was a peasant on the way to market or a former officer of the royal army.

Evariste's brother Alfred rushed to his brother's side when he heard of the shooting. Alfred was there to hear Evariste's last words: "Don't cry. I need all my courage to die at twenty." He died of peritonitis at 10:00 in the morning on Thursday May 31, 1832. His death was announced in the newspapers of Paris the following day. The record of the events consists of these newspaper articles and the coroner's report.

Many myths about Galois exist. One is that his work consists entirely of writing down his theories on the night before he died. As we've seen, he published during his life and this is not exactly the case. Some of this is based on the fact that there have been dramatizations of Galois' life, both books and movies. In addition, the details of the duel are very unclear. Who fired the fatal shot?

|

|

A well-researched biography due to Laura Rigatelli was published in Italian in 1996. Her theory is as follows. Galois was passionate about the republican movement. At one point, he tells his family if only a body would cause an uprising that would lead to the establishment of a republic and the end of the monarchy, he would gladly offer his life. Rigatelli proposes that the duel was a shame with the purpose of producing the body of a well-known revolutionary around which the republicans could circle. At the funeral, those in attendance would start an uprising. However, during the funeral, it became known that General Lafayette had died and the decision was collectively made to wait to riot until Lafayette's funeral, which would have a larger attendance. Galois' death had been in vain.

Mario Livio does not find Rigatelli's argument compelling, and takes a more traditional view, particularly focusing on the "infamous coquette" mentioned in Galois' first letter. He proposes that Galois' love interest, Stephanie, had been offended and that the duel was arranged by two of her uncles. This is in line with the main-stream idea that Galois "died in a duel over a woman." Livio's contribution is to speculate on particular names who were responsible for Galois' death.

Go to the next section: Galois Theory.

Last revised October 20, 2011.