Bacterial Meningitis: The Swift, Silent Killer

By Marie Hill

For Advanced

Composition, ETSU, Spring 2011

Marie Hill is a senior at East Tennessee State University

studying English and Education. She has also been in the medical field for 7 years

and is currently a pharmacy IV technician. Throughout all her years in medicine

she has never before seen the emotional devastation that she witnessed one week

while observing a high school English class.†

The parking lot of the

high school in Elizabethton, Tennessee was only half full when I pulled in on

that rainy and cold March day. As I walked through the cafeteria, on my way to

the school office, I noticed many students were absent.† Most of the underclassmen didnít show up for

school at all that day and the ones that did were distraught and quiet. The

juniors and seniors were more scared than sad and the concerned-looking

teachers whispered constantly to one another. The English class that I was

observing was very relaxed that day as the teacher did have the heart to press

the academic issue. The one thing on everyoneís mind, in the school and in the

close-knit Appalachian community, was the freshman boy, who had been there one

day and gone the next. His classmates, the four of them that showed up that

day, pointed out where he used to sit in their English class -- yet they

couldnít understand why he was no longer there. The teachers offered the

students an ear but they had nothing to say. Their silence echoed the deadly

silence of the disease that took away their friend.

The

Silent Killer

††††††††††† The young

man, whom Iíll call Jason for the sake of privacy, died from bacterial

meningitis. It is a condition that most would recognize upon hearing, but not

many could explain -- a result of its rarity.†

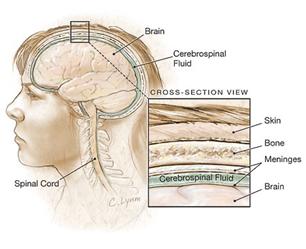

Meningitis is the inflammation of the meninges which are the membranes

that cover and protect the brain and spinal cord. The meninges also create a

barrier between the central nervous system and the bodyís blood; this barrier

is called the blood-brain barrier. Meningitis occurs when the meninges are

infected by bacteria, fungi, viruses, or other microorganisms. According to the

Center for Disease Control website, the microorganism begins in the bloodstream

and then moves on to the meninges where it breaks through via a weak spot. The

bodyís immune system responds to the invading organism by allowing the meninges

to become more permeable. This permits white blood cells and other fluids into

the central nervous system to help rid the body of the microorganism. This

influx of fluid causes serious inflammation of the membranes surrounding the

brain and spinal cord which limits the blood flow to these areas. This lack of

blood flow restricts oxygen to the brain which results in severe damage and

oftentimes death.

††††††††††† The young

man, whom Iíll call Jason for the sake of privacy, died from bacterial

meningitis. It is a condition that most would recognize upon hearing, but not

many could explain -- a result of its rarity.†

Meningitis is the inflammation of the meninges which are the membranes

that cover and protect the brain and spinal cord. The meninges also create a

barrier between the central nervous system and the bodyís blood; this barrier

is called the blood-brain barrier. Meningitis occurs when the meninges are

infected by bacteria, fungi, viruses, or other microorganisms. According to the

Center for Disease Control website, the microorganism begins in the bloodstream

and then moves on to the meninges where it breaks through via a weak spot. The

bodyís immune system responds to the invading organism by allowing the meninges

to become more permeable. This permits white blood cells and other fluids into

the central nervous system to help rid the body of the microorganism. This

influx of fluid causes serious inflammation of the membranes surrounding the

brain and spinal cord which limits the blood flow to these areas. This lack of

blood flow restricts oxygen to the brain which results in severe damage and

oftentimes death.

††††††††††† The microorganism which causes the most severe reaction

is the bacteria Neisseria

meningitidis, also known as meningococcus. Although meningitis can also result from

the invasion of fungi, viruses, etc., it is this bacterial form that is the

most dangerous. The meningococcus bacteria is a normal inhabitant of the human nasopharynx, the upper part of the

pharynx near the nasal cavity, and can reside there without infecting its host.

According to Pediatrics: Principles and

Practice, a textbook on pediatric medicine, around 15% of the human

population are carriers of the bacteria. This number can increase to 30% during

an outbreak of meningitis. The bacteria is spread to other  individuals by the

exchange of saliva and upper respiratory fluids through the acts of kissing,

coughing, and the sharing of food and drink. Once the bacteria is passed on,

conditions have to be perfect for it to find the weakness in the individualís

meninges and then for it to pass through that barrier. The initial symptoms of

infection are slight and may only include fatigue. However, fatigue can rapidly

progress to headache and stiff neck and then on to coma and death -- often

within 48 hours of infection. Around 3,000 cases of bacterial meningitis are

reported annually; 10% of those cases result in death and 1 in 5 survivors of

the disease will suffer from permanent damage such as an amputation, hearing

loss, scarring, or neurological damage.

individuals by the

exchange of saliva and upper respiratory fluids through the acts of kissing,

coughing, and the sharing of food and drink. Once the bacteria is passed on,

conditions have to be perfect for it to find the weakness in the individualís

meninges and then for it to pass through that barrier. The initial symptoms of

infection are slight and may only include fatigue. However, fatigue can rapidly

progress to headache and stiff neck and then on to coma and death -- often

within 48 hours of infection. Around 3,000 cases of bacterial meningitis are

reported annually; 10% of those cases result in death and 1 in 5 survivors of

the disease will suffer from permanent damage such as an amputation, hearing

loss, scarring, or neurological damage.

Diagram of

Meninges: Modern Guide to Health

Diagnosis and

Treatment

††††††††††† Diagnosing bacterial meningitis can be extremely difficult. Due to the

deadly nature of the disease, when a patient has symptoms resembling those of

meningitis, powerful antibiotics are administered immediately in an effort to

prevent death. A lumbar puncture can then be performed to test for the presence

of the bacteria. Since antibiotics have already been administered the chances

are moderate that most of the bacteria will be dead or dying and thence

unidentifiable. However, the benefits of early antibiotic administration exceed

the desire for definite diagnosis. If the test comes back identifying a

specific bacteria, then antibiotics will be given that are tailored towards

that particular strain.†††

††††††††††† The most important factor in

treating meningitis is time. The longer someone waits to seek treatment, the

poorer the outcome. The rapid progression of the disease requires immediate

treatment for the best possible outcome. Antibiotics are usually administered

at the first suspicion of meningitis. Antibiotics do not, however, resolve the

inflammation caused by the bacteria, which is the deadliest aspect of the

disease. It is imperative to control inflammation to avoid brain and

neurological damage. If intracranial pressure is high, administration of

medication is required to relieve the pressure and to allow blood to flow to

the brain and spinal cord. If blood flow is restricted too long then certain

brain damage and ††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††† ††††††††possible death will result. Steroids

can be administered, as well as a drug called Mannitol, both of which aid in

the reduction of inflammation. If the disease is caught soon enough, and

treated correctly, then full recovery is most likely the end result.††††

††††††††††† The most important factor in

treating meningitis is time. The longer someone waits to seek treatment, the

poorer the outcome. The rapid progression of the disease requires immediate

treatment for the best possible outcome. Antibiotics are usually administered

at the first suspicion of meningitis. Antibiotics do not, however, resolve the

inflammation caused by the bacteria, which is the deadliest aspect of the

disease. It is imperative to control inflammation to avoid brain and

neurological damage. If intracranial pressure is high, administration of

medication is required to relieve the pressure and to allow blood to flow to

the brain and spinal cord. If blood flow is restricted too long then certain

brain damage and ††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††† ††††††††possible death will result. Steroids

can be administered, as well as a drug called Mannitol, both of which aid in

the reduction of inflammation. If the disease is caught soon enough, and

treated correctly, then full recovery is most likely the end result.††††

Prevention

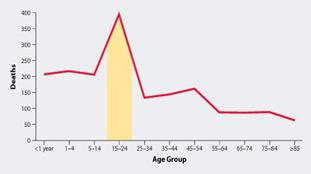

Bacterial Meningitis Mortality Rate by Age

††††††††††† So what can you do for protection against bacterial

meningitis? The most important thing to consider in the prevention of

meningitis is obtaining the meningococcal vaccine. There are several vaccines

available, some specifically for children and then those indicated for

adolescent and adult use only. The website for Menactra, a vaccine for

meningitis, states that vaccination of adolescents against bacterial meningitis

is highly recommended due to a decrease in immunity around the teenage years.

The vaccine has also become mandatory for many college students living in

dormitories due to the cramped living quarters among roommates, which increases

the chance for transmitting the disease.†

The vaccine is not a foolproof guarantee, but it can be the difference between

life and death.

†††††††††††

†††††††††††

There are also precautions that can be taken to help ward off

contraction of the disease. Since the bacterium is spread through saliva and

respiratory secretions, it is important to avoid drinking and eating after

other people. This is especially important to explain to †adolescents who tend to believe that their friends and their selves are

forever immune to any disease. Covering the mouth when coughing and developing good

hand washing habits will also help in warding off meningitis. The close

proximity of high school and college students, especially those in dormitories,

increases the risk for passing on the bacteria. An individualís immunity is at

an all-time low around adolescence because all of the infant vaccinations have

gradually worn off. Immunity then builds back up from exposure to various

microorganisms by the age of 25. According to the CDC these factors result in

the peak age for contracting bacterial meningitis to be from 15 to 25.

Therefore, it is imperative for adolescents to receive immunization which can

greatly reduce the chances for contracting the disease.

†Psychological Effect

††††††††††† I was off from work that Wednesday evening, relaxing on the couch

watching TV, when my cell phone buzzed with a text message. It was my

grandmother.

††††††††††† A boy at

Elizabethton High died today. They think it was bacterial meningitis. †

††††††††††† †Horrified, I immediately wondered if he was in

the class that I was observing. I pulled up Facebook, the best place to find

news, to see if anyone had posted about the incident. They had. Sadly, I

recognized the happy, intelligent face that was plastered all over the

internet. His ďmemorial pageĒ already had hundreds of followers.†

Jason went home from school with a headache

around noon on a Tuesday; his parents told the school that he became

unresponsive that evening, and was declared brain-dead by Wednesday morning.

The rapidity of the disease, and the lack of what seems to be serious symptoms,

is the cause of confusion and fear for those who have seen meningitisí

devastating outcome. It was a shock to the students, and especially Jasonís

friends, when they were all ushered into the gymnasium to be told of Jasonís

death and of the risk of those close to him contracting the disease. This event

set off something of a hysteria in the community as parents were extremely

worried about their own children contracting the disease. Many students and

teachers were given Rifampin, a strong antibiotic, as a prophylaxis for

meningitis. It eased their minds but did not heal their hearts as they mourned

for the happy and bright young man whose future was cut tragically short.†

Works Cited

Bacterial

Meningitis. Center

for Disease and Control. 25 March 2011. Web.

Bacterial Meningitis. Oskiís Pediatrics: Principles and Practice. Julian McMillan ed. 25 March

2011. Web. 348-56.

What is

the Menactra Vaccine? Website for Menactra, Vaccine for Meningococcal Meningitis.

26 March 2011. Web.