Invention Techniques

Two points in the writing process at which you are most likely to find mental barriers are in choosing a topic and starting to write. Fortunately, there are tools to help you through these rough patches called “invention techniques," which trigger your thought process and help you begin to think creatively about your topic (or to locate a topic, as the case may be).

The idea is to enter the writing process with some easy rules already set up for you – and no pressure. Invention techniques work best if you attempt them while relaxed and confident that any writing you complete at this articulation stage, as V.A. Howard calls it, will be productive writing. Don’t be afraid to use your imagination or even to write out things that don’t make a whole lot of sense at the time. While it is helpful to already have a subject in mind (a.k.a. a broad area from which you need to choose a topic), we have noted those techniques that can be helpful in choosing a topic from scratch.

Below are a number of invention techniques that have proven useful for writers in the past. Read through them, find a couple that suit your project and personality, grab a pen and paper, sit in a comfortable spot, and get started!

Invention Techniques List

Brainstorming

Freewriting

Focused Freewriting

Clustering

Aristotle’s Topoi

Larson’s Problem-Solving

Young, Becker, and Pike’s Tagmemics

Journalists' (a.k.a. Reporters') Questions

A Few More Tips for Invention

Brainstorming

For this technique you can use plain old pen and paper or some like to use the keyboard. Identify a general subject, and start making a list of items that are related to that subject, in no particular order, just as they come to you. Try not to make generalizations about the subject, but instead branch out into different avenues that subject might take.

The key to brainstorming is not to make any judgments about your ideas during your brainstorming session. Just write them down. This is the time to let your imagination run wild. Some people like to turn off the computer monitor so they won't be tempted to look at the screen and get distracted while they're brainstorming. After you have a healthy list, take a look at it – what can be grouped together? What relationships exist among items on your list? Do any of the relationships strike you as interesting? Perhaps worth pursuing as a topic?

Brainstorming can be particularly useful when done as a part of a writing group – each person comes at a subject from a unique perspective, so your brainstorming session can only be enriched by adding others. Try to allow at least 15 minutes for your brainstorming, because it can take a little while for your brain to get going.

Back to Invention Techniques List

Freewriting

Freewriting can be especially useful once you think you've located a topic that you want to explore different aspects of. The only condition placed on freewriting is time. Give yourself a set amount of time (10 to 30 minutes is a good amount) and write just about anything. Also, keep writing no matter what. If you get stuck, write the last word over and over again until you think of something else. In any case, do not worry about spelling, grammar, or even the logical flow of paragraphs, sentences, or anything you write. No one has to see this, so what are you so afraid of? Freewriting works best as a warm-up to a more focused writing session, but don’t crumple up and throw out your freewriting work – you never know when a valuable insight for your paper might show up.

Back to Invention Techniques List

Focused Freewriting

This is exactly like regular freewriting, except you limit your subject matter to the aspect of your topic you think might be most promising (you can also do focused freewriting to try out the promise of several different possibilities). Start writing a draft or get ideas of where you might find sources. Again, allow 10-30 minutes for the session, and write anything about your chosen focus that pops into your mind. If you find your mind wandering, you can write down the straying thought, but try to refocus by rewriting your subject/topic until a related thought emerges. Focused freewriting is especially helpful for developing a working thesis out of a topic.

Back to Invention Techniques List

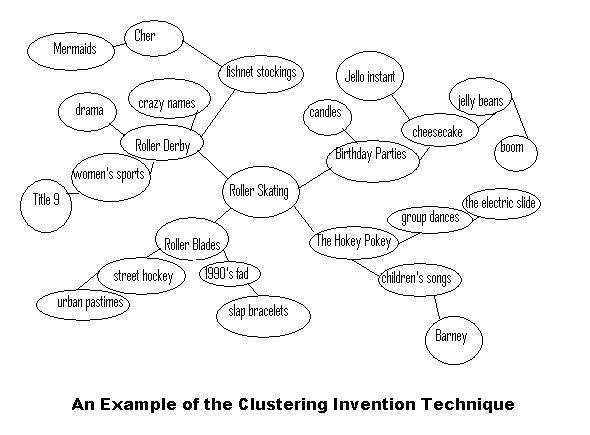

Clustering

Clustering is a way to visually organize your ideas. As the name implies, in clustering you arrange your thoughts in "bunches" according to similarities. Basically, you begin with one word or phrase that explains a prospective topic. Write that in the middle of a sheet of paper. Then, draw a circle or box around that word. Then, begin writing down, around the central word, other words or phrases that you think of when thinking about the topic. You can branch out as much as you want; in fact, the more you branch out and associate words with words and concepts with concepts, the more potential topics of discussion you will end up with. Below is an example of a clustering effort:

Back to Invention Techniques LIst

Aristotle's Topoi

This invention technique has you place your subject in different "topoi," or places, where you then ask different questions about it in the context of each topoi.

Here are the five topoi:

- Definition - How does the dictionary define your subject? How do you define it? What are some examples of it? Can you classify it in any way?

- Comparison - What is your subject similar to and different from? Is it better or worse than anything you can think of?

- Relationship - This topoi covers cause and effect of your subject. What causes it to happen or to come into being? What does your subject have an effect upon?

- Testimony - This refers to stuff that's been said about your topic. What types of books, music, and movies are about it? What do they say? What opinions exist about your subject?

- Circumstance - This refers to the circumstances surrounding your subject. What conditions influence your subject or must be in place for it to operate? What conditions may prevent it from happening or working? Are there any geographic locations in which it works well?

Back to Invention Techniques List

Larson's Problem-Solving

This is a particularly good method for generating a working thesis from a well-narrowed topic. It is a set of eight questions that encourage you to look at your topic as a problem that can be solved (hence the name). The idea is to find competing or contradictory characteristics of your topic and get the conflict out on paper. Here are the questions to ask yourself:

1. What is the problem?

2. Why is it a problem?

3. Why do we need a solution, and who (or what) would benefit from a solution?

4. What are the most critical reasons a solution is needed?

5. What steps might get us to a solution?

6. What foreseeable consequences might arise from the proposed solution(s)?

7. How does each alternative solution differ, and how are they the same? (Allen F. Repko terms this "finding common ground." See Chapter 11 for more discussion of this concept.).

8. What is the best solution?

When you've answered all of these you should end up with a much better idea of possible "so what" questions and paths of argument to take.

Back to Invention Techniques List

Works cited: Repko, Allen F. Interdisciplinary Research: Process and Theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2008.

Young, Becker, and Pikes Tagmemics

This is an invention technique derived from a 1970 book proposing a new theory of rhetoric, called Rhetoric: Discovery and Change. Pike was the main thinker here, and wanted to propose a theory of rhetoric that concentrated less upon a “you against me” mode of argumentation than on a way of bringing conflicting sides together. In other words, if rhetoric worked so that each opposing side acknowledged and understood how the other’s views compared to and fit into his own, then a solution could be reached more readily. (Compare this to Repko's notion of "common ground.")

Journalists' /Reporters' Questions

These are basic "W" questions (Who, What, Where, When, Why, and How?) applied to your own subject/topic. For example: Subject = House Cats.

Who deals with issues related to house cats?

What do house cats do?

Where are house cats most commonly found as pets?

When was home decor featuring house cats most in vogue?

Why are house cats associated with spinsters?

How do house cats find their way home?

The neat thing about journalists' questions is that you can get really creative in the questions you generate, even though at first it looks as though you are only asking 6 questions (e.g., who is a house cat, what are house cats, etc.). Certainly you could start out by simply inserting your subject into the question, but it is a lot more productive (and fun) to build more interesting questions. As with any invention technique, half of the questions you produce might be useless in your research, but they can be extremely helpful stepping stones toward great research ideas! (And sometimes good for a good laugh or two, as well!)

Another way you can use the journalists' questions is by turning your subject into an adjective and then asking the questions, leaving them completely open-ended. This alternative is best for narrowing very broad subjects.

Back to Invention Techniques List

A Few More Tips for Invention and the Early Stages of Drafting

- Remember, you are first writing for yourself, thinking on paper. Don't worry about making a stellar sentence or paragraph at first. This is what a rough draft is for - to help YOU comprehend your research and make it all make sense.

- There is no law saying you have to start at the very beginning. Yes, it is a very good place to start for songs, but not always for seminar papers and other academic assignments. If you need to start in the middle of your paper, writing a section of the argument first, do that. Chances are you will end up revising that section once the rest of your paper starts coming together, but that's okay. Start writing whatever part of the paper gets you writing.

- Think out loud. Verbally present your ideas to your friend, your cat, your daughter - anyone who is a captive audience. If no one is around, talk out loud to yourself. Sometimes getting the whirling thoughts out of your brain and into the open can be the catalyst that gets your writing moving.

- Carry around a digital recorder for random moments of clarity. Be ready to record your thoughts as they pop into your head. You might look a little funny to others, but you’ll get over it (chances are you look a little funny to others anyway).

Back to Invention Techniques List

The information in this page is based upon the following resources: